At the outset of the 1960s, the popular press generally divided into two camps. There were the respectable mainstream publications such as Life, Look, Time and The Saturday Evening Post, which covered contemporary news. And then there were the so-called “women’s magazines,” which included such varied publications as Vogue, Ladies Home Journal, Cosmopolitan and McCall’s. In contrast to the big boys, the lady mags covered soft news, frothy subjects such as celebrities, fashion and family.

Because women comprised the bulk of their audience, the movie magazines were lumped in with the women’s magazines, though they were a distinct subset unto themselves. A special breed of magazines invented by the film studios, the movie magazines were originally intended as a publicity tool. Providing a template upon which Us Weekly and In Touch would capitalize later, the movie magazines covered the misadventures, tribulations and lifestyles of television and film stars.

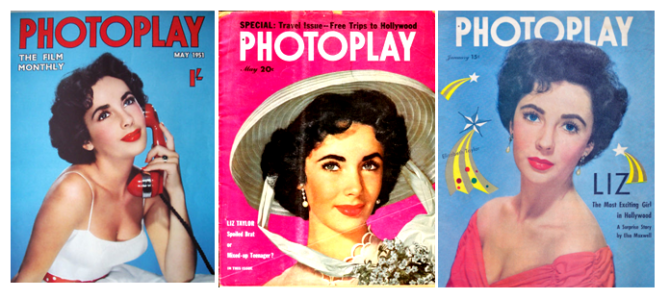

At the height of their popularity, there were upwards of forty publications, including Photoplay, Motion Picture, Modern Screen, and TV Radio Screen. They had little in common with Ladies Home Journal and Vogue.

Most often, the movie magazines were characterized as “tabloids,” but even this classification was misleading as the movie magazines were not tabloids in the truest sense. The term “tabloid” originally denoted periodical size but it had, by the 1960s, become synonymous with down-market sensationalized, special interest magazines.

In a report for the April 1969 issue of Playboy, Reginald Potterton cataloged the preoccupations of the mainstream tabloids: Justice Weekly “boasts an editorial obsession with just about every form of deviation known, short of bestiality and necrophilia; while Confidential Flash, the National Informer and Midnight range over as many bases as possible but incline toward ‘straight’ sex and horror-violence.”

While, in time, the movie magazines would push the boundaries of acceptable celebrity reporting, they never went to these extremes. The world they depicted was populated by glamorous stars seeking comfort in love, family and faith. Even back in the 1960s, celebrities seemed to want nothing more than to be normal. They longed to be Just Like Us.

When I was 11, I was a devoted follower of “The Mickey Mouse Club.” I don’t remember reading many fan mag pieces on the Mouseketeers, but I can vividly recall waiting impatiently every week for the series of articles about Walt Disney that appeared one year in The Saturday Evening Post. For me at that age, “Uncle Walt” was the biggest celebrity of all. (He was soon succeeded, however, by Yul Brynner.)

Biographers don’t always take into account how important the influence of the popular press can be on their eminent subjects’ childhoods. Thanks for reminding me.

Pingback: movie magazines: a brief history in several parts (part 2) | finding jackie