(16 may 2006/23 september 2010)

Long, long ago, back in the dark ages before US Weekly, the movie magazines reigned supreme. A special breed of tabloid that the film studios cunningly created in the 1920s as a publicity tool, the movie mags spent their first 40 years offering puff pieces on everyone’s favorite stars. But, because it is often hard to make money being nice, in the late 1950s, the tone of their coverage took a salacious turn and veered towards the tantalizing cocktail of glamorous lives, naughty headlines and provocative photographs that beckons to us from newstands to this very day.

Tabloids, as a genre, engender little loyalty, so the industry has always depended upon newsstand sales to an extraordinary extent. To this end, movie magazine editors rushed to find celebrities who exercised broad appeal and would hold the public’s interest over long periods of time. Three months was considered an eternity. Thirty years had never before been done.

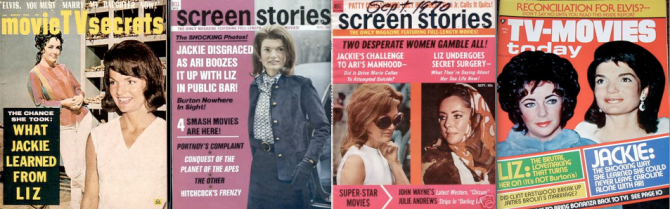

Much as popcorn kept movie theaters afloat after the advent of television, so Jackie Kennedy salvaged the movie magazines. She never starred in a movie but she featured in the movie magazines to such an extent that in 1962, Variety enthusiastically hailed her as the “world’s top box office femme.” The prevailing editorial policy of all of the 40+ movie magazines then became this: to regularly feature the First Lady alongside “any lady or gentleman of the screen and television who misbehaved.”

Among the ladies and gentlemen misbehaving at the time, Liz Taylor was queen bee. Thus, despite the absence of any legitimate connection, Liz and her then-husband Richard Burton would become Jackie’s “magazine relatives.” Ultimately, the Jackie-Burton-Liz tabloid triangle pervaded the national consciousness to such an extent that it created among magazine readers a Pavlovian response to the three principle players. According to sociologist Irving Schulman:

If new photographs worthy of inclusion at deadline were not to be had, art directors arranged jigsaw cutouts for Jackie-Burton-Liz, and in a very short time indeed a national conditioned response was established. Purchasers who saw a photograph of Jacqueline Kennedy would think immediately of Elizabeth Taylor and what she was doing; conversely a photograph of [ . . . ] Elizabeth Taylor would conjure up an image of Mrs. Kennedy.

The Jackie-Liz connection would become so integrated into the popular culture that in the Hollywood treatment of the Jackie story, The Greek Tycoon, the lead female character was named “Liz.”

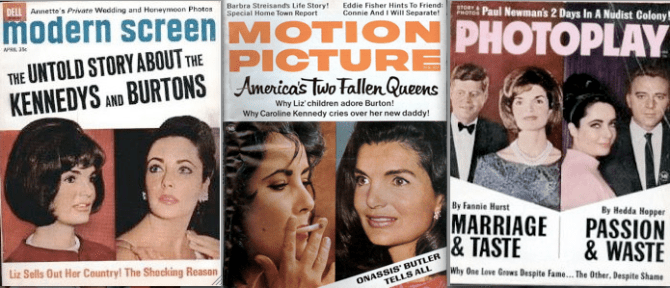

In the beginning, particularly during the Kennedy administration, the movie magazine coverage remained somewhat circumspect. The couples served as simple foils for one another; the Burtons’ racy exploits emphasized the Kennedys’ elegance while Jack and Jackie’s élan exaggerated Burton and Liz’s decadence. In the fall of 1963, the question of the Kennedys’ “Marriage & Taste” versus the Burtons’ “Passion & Waste” was of such critical social import that Photoplay gave it major coverage.

In retrospect, it is not surprising that this circumspection ceased with the death of JFK. As Jackie marched into single womanhood, the tabloids switched course and focused on the remaining threesome- cropping cover photos and manipulating gossip to suggest romantic intrigues, clandestine meetings, and unorthodox sexual proclivities. Richard Burton and Jackie Kennedy may never have held hands, but thanks to clever editors and decoupage, on countless magazine covers they did.

The tabloids intentions here were completely pure: they sought to unite “Jackie” with the Burtons because “It would truly be a new, fun, fun world for Jackie– for the Burtons are fun, fun people.” And, really, who didn’t want Jackie to have fun?

Editors could not have created more different and more profitable characters to mash-up. Women loved to hate “Liz,” an actress who seemed constantly on the brink of personal disaster; they simply loved Mrs. Kennedy. In the words of pop-philosopher Wayne Koestenbaum, “Liz was trash; Jackie was royalty.” It was the perfect mix.

In the American consciousness, Jackie and Liz presented two entirely different versions of femininity in practice. What this translated into was Jackie being the woman everyone should aspire to be and Liz being the woman no woman would want to become (never mind that Liz seemed to always be having a hell of a lot more fun).

This dichotomy is nowhere more vividly exemplified than in the 1962 magazine, JACKIE and LIZ. The commemorative opens with a page that explains the editors’ reasons for comparing Jackie and Liz: “They shine in completely different constellations and exert a completely different emotional and moral effect upon us… To compare them [ . . . is] a way for us to examine the natures of the stars we create, and in the process discover something about ourselves.”

What we, the reader, should discover is clarified in a simple headline on the same page: “LIZ TAYLOR: A Warning To American Women; JACKIE KENNEDY: An Inspiration to American Youth.” Jackie was “WOMAN OF THE YEAR,” “Mistress of the Washington Merry Go-Round,” and “First in the Hearts of Her Countrymen.” She “KEEPS HER MAN HAPPY,” is “SURROUNDED BY LOVE” and only “Leaves Her Home For Service.”

In very stark contrast, “Liz” was the “SENSATION OF THE YEAR” and “STAR OF THE ROMAN SCANDALS.” “A Woman Without a Country” who was “Caught in the mad Marriage-Go-Round” and “SURROUNDED BY FEAR,” she faced “A THREATENING TOMORROW.”

I know no women who would welcome a threatening tomorrow. Life is hard enough as it is.

In JACKIE and LIZ, Jackie was lifted up as a shining paragon of virtue and good. To gossip columnist Fanny Hurst, her place in people’s affections was a barometer of the national well-being. So long as we all loved Jackie, the world would be ok.

In contrast, through “unsavory Taylor-Burton headlines, the shabby stories of shabby lies, of multiple marriages, infidelities, divorces, broken homes, displaced children,” Liz- heaven help her- had “steered her sex toboggan down a dangerous run.” A message that was, no doubt, not lost on readers whose own marriages might be lacking “the fire of passion” and women who might be tempted to follow Liz’s less traditionally feminine example by steering their own toboggans along her perilous path. Let there be no doubt, “Roman Scandals” were not welcome here.

Collectively, the tabloid narrative implies a sexual rivalry between the two women. When Jackie, allegedly rankled by Liz’s affair on the Cleopatra set, didn’t attend the movie’s Washington premier, TV Radio Mirror rushed to declare it: THE DAY JACKIE ‘SLAPPED’ LIZ! In the article, prudish Jackie frowns upon Liz’s amorous exploits and Liz’s doings appear spectacularly more whorish when on parade before Jackie’s puritanical restraint. Yes, Liz’s indiscretions were startling by contemporary standards, but she appears downright depraved beside Jackie’s sanctity.

In later years, all this would change. With“Jackie’s” slide toward Greek decadance, the rivalry would continue to dominate newsstands but the headlines would grow increasingly sexual and provocative: AMERICA’S TWO FALLEN QUEENS; ONE NIGHT WITH JACKIE’S HUSBAND MAKES LIZ’ DREAM COME TRUE; THE NIGHT ONASSIS TURNED TO LIZ; JACKIE DISGRACED AS ARI BOOZES IT UP WITH LIZ IN PUBLIC BAR; TWO DESPERATE WOMEN GAMBLE ALL; LIZ’ PREMARITAL HONEYMOON PLANS INVOLVE JACKIE’S HUSBAND!

Jackie’s very appearance in the movie magazines suggested a massive shift from their original function as an advertising vehicle for motion picture stars. Both Liz and Jackie were exaggerated icons, however, Liz, an actress, was in fact selling a product– herself and her movies. Because Jackie had nothing to hawk, her life itself was turned into a movie for the public’s entertainment. By the early-1960s, it was playing out on newsstands all across the country.

In time, the differences in the unique relationships readers developed with both women would become more apparent. Liz’s connection to the public derived from total revelation. In Life the Movie, film and culture commentator Neal Gabler succinctly catalogs Liz’s shifting societal role:

Taylor’s early appeal as a life performer was her willingness to expose her private sexuality, first with [Eddie] Fisher and then with [Richard] Burton, and to provide a voyeuristic charge for those who read about her. Her later appeal, when she was no longer a sex symbol, was her willingness to expose her dysfunctions as melodramatic entertainment: her ballooning weight and subsequent diets, her drug problems, her vexed marriages and romances, her various illnesses.

In contrast, Jackie’s audience was tantalized by what she withheld. Her adamant refusal to reveal herself or her private life created a vast expanse of ignorance, which proved fertile ground for wildly speculative assertions and implausible fantasies. Because Jackie refused to participate in the tabloid pageant, the magazines reached out to readers—inviting them to select a wedding dress for Jackie’s remarriage, to suggest a hairstyle, and to pass judgment upon her hem lengths. In a manner eerily evocative of American Idol, the movie magazines fostered the public’s sense of interactivity in Mrs. Kennedy’s life. After her remarriage in 1968, Motion Picture even invited readers to vote to “BACK JACKIE,” as if their support would have a real effect upon the new Mrs. Onassis.

In American culture, Jackie acted as a tabula rasa, onto which everyone from little girls to frustrated housewives could project their fantasies of glamour and romance. As an Onassis acquaintance once said: “Jackie was nothing; an ordinary American woman with average tastes and some money. She was a creation of the American imagination.” Yet, within the tabloid culture, Jackie heralded a new age, in which “an ordinary housewife writ large” could become a star. And as that great arbiter of celebrity- and friend of both Jackie and Liz- Andy Warhol once said, “More than anything people just want stars.”

© faith e.

Fascinating! I was relieved to see, at the grocery store yesterday, that Angelina Jolie is back on current tabloid covers. After endless months of reality star nobodies dominating the check-out lines (seriously, why does anyone care about Jon and Kate Kate?), it was about time an actual, honest-to-goodness star made it there. Also, it seems like these days, instead of pure Jackie vs. salacious Liz, it’s girl next doorJennifer Aniston vs. bad girl Angelina Jolie, eternally fighting over Brad Pitt as God and Lucifer quarrel over the souls of men.

i’ve long had a theory that angelina and jen are the elizabeth taylor and debbie reynolds of today. which would make brad pitt eddie fisher, which is just kind of awesome.

So, which one of the Brangelina brood will grow up to become today’s/tomorrow’s Carrie Fisher?

that, my friend, is the million dollar question.

Pingback: the formal acceptance of fath caroline eaton | finding jackie

Pingback: biographers love to talk about process | finding jackie