Socialite Alexandra Webb provides the most vivid portrait of Jack and Janet Bouviers’ relationship: “Janet married him because his name appeared in the [Social] Register. He married her because her father operated a bank. She was a bitch and he was a bastard, and in the end both were disillusioned.”

An entire marriage cannot be adequately encapsulated in a pithy paragraph, but Webb’s is an assessment in which the elements that would define the life of the Bouvier’s eldest daughter are all present: society, power, money. This is what she would be born into, a world where, particularly for women, the attainment and the keeping of social status, power, and money were one’s raison d’etre. That was the fundamental lesson to be distilled from the lives of Janet and “Black Jack” Bouvier.

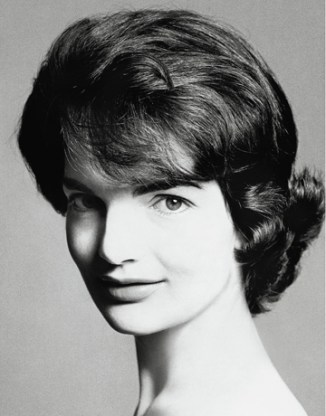

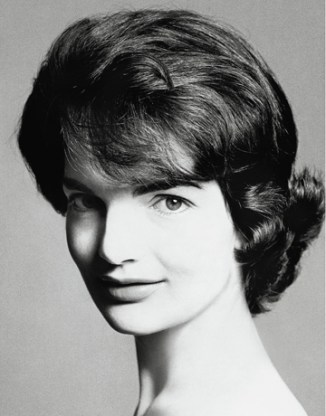

Jacqueline– pronounced Zhak-leen (“rhymes with Queen,” the Kennedys would tease)– adored her father, a dashing rake with matinee idol looks and a year-round tan. He was to have the greatest impact upon her early life, but his influence had a dark side. Black Jack was obsessed with the superficial, profligately spent money he did not have, and was always, always an incorrigible letch. From him, Jacqueline inherited her widely-spaced eyes, a propensity for retail therapy, and an indefatigable love of sexual gossip. At school or social functions, much to his daughter’s amusement, Black Jack would point out the women in attendance whom he had bedded.

Is it any wonder she went on to marry one of the century’s great bed-hoppers? As John “Demi” Gates, an early admirer, later admitted: “She had all the wrong standards, all the wrong standards, and yet she became something very special in spite of this.”

For all his faults, Black Jack lavished Jacqueline with praise. In his memoir of her youth, Jacqueline’s cousin John Davis wrote: “At Bouvier family gatherings it was almost embarrassing to hear Jack extol Jacqueline’s qualities before everyone.” In her father’s eyes, she could do no wrong. This came in stark contrast to Jacqueline’s relationship with her mother.

Janet Bouvier has not fared well with biographers. Thanks in large part to the damning testimony of a former maid, she emerges as little more than a money-grubber, bitch-slapping everyone who got in her way. But, if we’re being objective, Janet was in an impossible situation. With two young children, she found herself married to a broke, womanizing alcoholic. This was not what she had signed up for. After a newspaper published a photograph of Black Jack holding hands with another woman while Janet stood ignorantly by, blithely beaming, the couple separated. After the divorce– a shocking, ostracizing action for anyone, much less a Catholic, in the 1930s– Janet had to solicit financial help from her parents, a humiliating experience for a woman already reputed for her sense of dignity and implacable pride.

A meticulously mannered, socially ambitious woman, Janet demanded perfection from her daughters– particularly her eldest. Janet’s daughter Lee later mused: “I don’t think [Jacqueline] ever disliked my mother as you’ve heard. I think that she was always grateful to her because she felt that she had intentionally enlarged her world– our world– for our sake.” If Black Jack had failed her, Janet would not fail them. She knew the pressures her daughters would face as they grew up in Society and she tried, in her own way, to equip them to meet those challenges, drilling into them, both in words and by example, a belief that would underpin their actions from then on: that, for a woman, financial security was foremost. Janet had been forced to crawl back to her parents and admit her failure. She hoped to protect her daughters from ever having to endure such an indignity by instilling in them an almost pathological fear of penury.

While Janet’s aims were benevolent, her methods were not always kind. Jacqueline’s eerie resemblance to Jack Bouvier inevitably provoked Janet’s temper. The young girl was berated for her “messy” hair, large hands and feet, and broad shoulders, which were perceived early on as liabilities in the marriage game. During the divorce, a disgruntled Bouvier maid testified on Black Jack’s behalf that she had seen Janet hit her daughters. Even Jacqueline’s sister Lee, considered by many to be the family beauty, admitted: “there was an awful lot of criticism.”

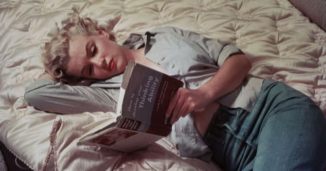

By the time she was a teenager, the young Miss Bouvier had absorbed the lessons of her parents—the longing for lovely things, the craving for cash, the need to catch a husband— and established a rigid, protective distance from the world. There were pieces of herself she refused to share, instead retreating into what one acquaintance characterized as “a world of manufactured dreams.” She formed a nearly impenetrable persona, cultivating a seductive, breathy voice that lent her the air of a simpleminded flirt. It was a convincing act, but the stage whisper hid an archly intelligent, imaginative woman.

Acquaintances do not recall Jacqueline as warm and friendly, but the words “sympathetic,” “understanding,” and “thoughtful” crop up with surprising frequency. A picture emerges of a gentle, tenacious girl, both deeply sensitive and alarmingly tough. A classmate later recalled, “She was so striking. She had such a spirit, such a dignity, and a bearing, and a feeling, that while none of us would come up and speak to her, we all knew who she was.” She would go on to attend Vassar, spend a year at the Sorbonne, tour Europe twice, graduate from George Washington University, win and decline Vogue’s prestigious Prix de Paris prize, and land a job as the “Inquiring Photografer” at the Washington-Times Herald. All by the age of 23. It was a daring route: “For a young woman of our background and time,” recalled Jacqueline’s friend Vivian Crespi. “It was still considered almost revolutionary to go to college, let alone have a career.”

Jacqueline did all of this and yet, still she was floundering. On January 21, 1952, the Times-Herald reported Miss Bouvier’s engagement to John Husted. Before the engagement was even announced, she had doubts and began distancing herself; by March, the couple had split. She later admitted, “I knew I didn’t want the rest of my life to be [in Newport]. I didn’t want to marry any of the young men I grew up with– not because of them but because of their life.” She did not know what she wanted and such reflections belied the increasing pressure to marry and to marry well. In the intervening years since the Bouvier’s divorce, her father had only suffered further financial losses, and since Janet’s remarriage to Hugh Auchincloss, Jacqueline was merely wealthy by proxy. She had no money of her own.

Though Jacqueline’s choices up to this time—college, travel, a newspaper job—had diverted from the typical debutante trajectory, in the end there seemed to be but one path. No matter how long she deferred it, she had to marry and she would likely marry someone from her class. But, as evidenced by the busted up Husted engagement, she would not settle. She wanted excitement and adventure and love. And she had already set her sights on someone else.

Congressman John Kennedy had casually entered Jacqueline’s life a few times before. In a 1948 letter, penned on a bumpy rail car, the Vassar sophomore wrote home that a “tall thin young congressman with very long reddish hair, the son of a [former] ambassador” had been insistently flirtatious with her. It would be the spring of 1951 before John and Jacqueline were finally introduced at a dinner party hosted by Charles and Martha Bartlett. The Bartletts hosted another party on May 8, 1952, which both Jacqueline and John Kennedy would cite as the advent of their relationship. Kennedy later told Time magazine that Jacqueline had impressed him that evening, “So I leaned over the asparagus and asked her for a date.”

Theirs would be a frantic courtship, unfolding as Kennedy jetted back and forth between Washington and Boston during his Senate campaign. “He’d call me from some oyster bar up on the Cape with a great clinking of coins,” she said, “To ask me out to the movies the following Wednesday . . .” She loved him, but she wasn’t sure she wanted to marry, a quandary the Senator shared. Aileen Bowdoin Train mused: “I don’t think it was indecision about him. She was worried about being taken over by politics and another family, because she always wanted to be herself, and I think that losing her own personality was what she was most worried about.”

In his own way, Jack Kennedy was a radical choice. The Bouviers themselves didn’t have the fanciest of family trees, but they flattered themselves they were Old Money. And though the Kennedy social stature had been improved by a decade of civic duty, theirs was still a fortune tainted by the nouveau riche entrepreneurial stink of bootlegging and Hollywood. A matter not helped by the fact that Jack Kennedy was an Irish Catholic politician. He wasn’t from Tammany Hall, but he wasn’t quite far enough from it for Newport society. Thus, it was a marriage someone like Janet Auchincloss would have seen as a decided step down. And perhaps, to Jacqueline, that just made it all the more appealing.

At the time she said, “Since Jack is such a violently independent person, and I, too, am so independent, this marriage will take a lot of working out.” Though Kennedy was deeply attracted to her intelligence and wit, his compulsive unfaithfulness and the “violently conflicting signals” he sent further eroded Jacqueline’s self-image and deepened her emotional defenses. She made every effort to impress her new husband, reinventing herself as an elegant, Givenchey-clad political consort, but try as she might, Jacqueline could not capture his undivided attention. In a 1968 letter to Cecil Beaton, Jacqueline’s sister admitted: “Jack used to play around & I knew exactly what he was up to & I would tell him so. And he’d have absolutely no guilty conscience & said, ‘I love her deeply & have done everything for her. I’ve no feeling of letting her down because I’ve put her foremost in everything.’”[18] Jacqueline hid the full extent of her unhappiness. Chuck Spaulding, a friend of the couple, observed: “She has a toughness, like a fighter who doesn’t go down, but gets hurt. I think she probably suffered to beat the band, but nobody ever saw the hurt.”

The complexity of the Kennedys’ relationship has become legendary. In January 1961, even Time had to admit that “[i]n the gossipy circles they moved in, it was an open secret that the Kennedys’ married life was far from serene.” It didn’t help that within months of their wedding the couple were beset by the first in a string of difficulties that would have tested even the most solid relationship: John Kennedy’s eight-month incapacitation from back surgery in 1954, a series of miscarriages, a still birth in 1956, the subsequent brief separation, and the sudden death of Jacqueline’s father, who had spiraled into a dismal tailspin of bankruptcy and booze. The 1957 birth of their daughter, Caroline, solidified the Kennedys’ shaky bond, but their relationship would always be fraught. Following his high-profile appearance at the 1956 Democratic Convention, John Kennedy spent the years prior to the 1960 election traversing the country, campaigning on behalf of fellow Democrats and laying the foundation for his presidential bid. Jacqueline once complained that she rarely saw him for more than two days in a row. When she found herself six seats down from him at a campaign function, she quipped: “This is the closest I’ve come to lunching with my husband in four months.”

Jacqueline once characterized herself and her husband as icebergs, “with the greater part of their lives invisible. She felt they both sensed this in each other and that this was a bond between them.” It was also an obstacle. In the mid-1950s, according to one of John Kennedy’s female confidants, “He just couldn’t stand her. That’s all I got. I mean he couldn’t understand or stand her at all at that stage.” And yet, he was still fascinated. At a Washington birthday party, Kennedy confided to Priscilla Johnson Macmillan that he only got married because he was thirty-seven, and if he remained a bachelor people would think he was “queer.” As Macmillan recalled,

Throughout their marriage, the couple would struggle to overcome what Jacqueline once referred to as “an emotional block” between them, a block that arose because “his love had certain limitations and hers was total.”Jacqueline would later say that in her mind she could “drop this curtain” over unpleasantness, blocking out pain through sheer willpower. Kennedy’s ascension to the Presidency would only further test her resilience.

It’s dangerous to reduce a person to a single story. We are all more complex, more nuanced than any handful of anecdotes could convey, but there are two accounts that stand out among the rest to capture the extremes of Jacqueline’s personality. The first comes from a female acquaintance, who once complained of Jacqueline: “She had so many sides. She behaved very capriciously. She’d be very seductive to a man at a party, sitting next to him, and then stub her cigarette on his hand.” The second, from Jacqueline’s housemate during her year at the Sorbonne: “Jacqueline had enormous strength of character, but she also had her weaknesses. It wasn’t always easy for her. When you’re the kind of person who wants only to be strong– well, she suffered from this. She couldn’t accept her own frailties.”

One story captures the hidden audacity, the downright grittiness of the woman the world would later know as “Jackie O”; the other, the sensitive fragility of a woman who was never nearly as tough as she looked.

You must be logged in to post a comment.