tracy weiner- whose writing biography class constitutes the sole semester of biographical training that comprises the biography concentration of my masters degree in the humanities- once said: the biographer has the power to control perception.

that sounds a bit maniacal, but consider the case of the horrible things jackie allegedly said at random deathbeds.

as a biographer, i’m under no moral obligation to discuss the horrible things jackie allegedly said. i can’t remove the random deathbeds from jackie’s history, but i can erase the horrible things she may have said there. i can leave them out altogether and you’ll never be the wiser.

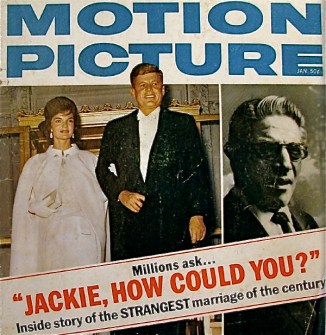

i can just as easily bring them up without any context and leave you thinking jackie’s a callous, intolerable bitch. i can make you ask, jackie, how could you stand at a random deathbed and say such a horrible thing?!

or, i can contextualize the random deathbeds and show you how the horrible things jackie said there were entirely warranted and were, in fact, not so horrible.

i can make the horrible things jackie allegedly said at random deathbeds look entirely within her character or completely out of it.

i can also cushion them with the word “allegedly,” so before you even hear that jackie said horrible things at random deathbeds there is already, in your mind, some shadow of doubt.

when it comes to your thinking on the horrible things jackie said at random deathbeds, i hold great power.

(presuming, of course, that you care about jackie and that it is of some importance to you whether she was one to say horrible things in general and at deathbeds in particular.)

as is nearly always the case, the story of the horrible things jackie may or may not have said at random deathbeds is important not so much for what it says about jackie as for what it says about us.

the core revelation of tracey weiner’s writing biography class was that there are practices- be that chronology, word choice or whatever- that biographers use to manipulate our thinking on a subject and impose their own beliefs.

though non-fiction masquerades under the auspices of being entirely true, it truly isn’t. it’s perception. and opinion. and a whole host of personal biases.

and so biography is maybe as much about the biographer as about the subject. within the genre, there’s a great deal of clucking over this. it’s often labeled a handicap, though i don’t think it always is.

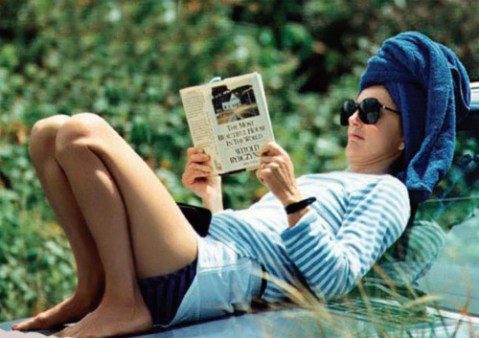

i crave examples of female adventure, of women deviating from the expected.

from the first, that is the lens through which i have seen jackie. it’s a view that’s been missing in both the biographical record of her and her iconic persona and one that, i think, is integral to our understanding of who she was. it can’t be a coincidence that, time and again, when discussing her publicly, her children evoked her love of adventure.

i look upon hers as the most significant female life of the american twentieth century. i date that significance to the onassis years. and i base it on her fictional alter ego’s narrative journey through tabloid magazines.

all of that deviates from pretty much every existing line of thought.

that heroine though – the rich kid from newport who married a pirate and moved to greece and allegedly said horrible things at random deathbeds- she, my friends, is completely kick-ass.

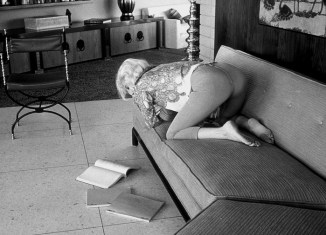

but people like their icons boring. they like to play it safe. they prefer that their former first ladies be quiet, kid-gloved and kitten-heeled rather than wandering capri barefoot and without a bra.

even jackie’s biographers are skittish when the story strays far from her iconic image. in the case of the horrible things jackie allegedly said at random deathbeds, they hand over the anecdote like a hot potato, thrusting it upon the reader at a chapter’s end.

the schelesinger tapes evoked a similar sense of disquiet. jackie was catty! jackie had opinions! oh my god, jackie held a grudge!

as far back as the 1960s, when confronted with evidence of her humanity, the world has recoiled.

in taking on a set series of meanings, our cultural icons are supposed to be safe and sterile and silent. they are not meant to change but rather are fixed images, trapped like han solo in carbonite.

culturally, this is an important process. but it’s also one that biography should counteract.

the biographer has the power to change perception.

but can the biographer rewrite a myth?

(photos by george barris)

You must be logged in to post a comment.