fragments, in no order, in and out of time.

***

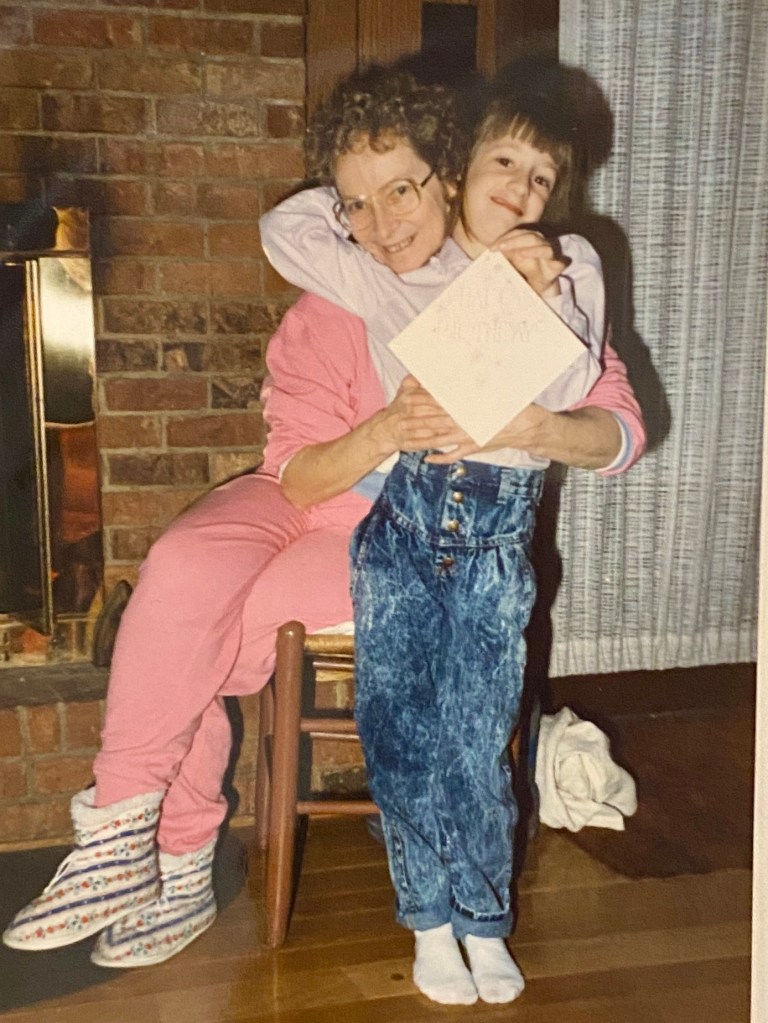

but then you always knew exactly what you wanted to be, burvil says.

i’m watching an orange cat on an adjacent roof top stretching out in a patch of sunshine while another cat, a black one- who obviously likes the orange one more than the orange one likes it- tries to insinuate itself into the periphery of the spot of sunshine in which the orange cat is lying when i hear her say this. when she drops this revelation that i’ve always had my whole life figured out.

and i say, shut the front door.

something i have never thought, much less said aloud, in my life and certainly not to my grandmother.

but it was inconceivable that there could be any amnesia regarding how completely clueless i have been about how i wanted my life to look, how it took me, like, DECADES to convince myself that what i write has value and that my life could and should be the strangely impossible wonderfully weird thing that it has become.

apparently burvil had this idea that everyone else knows what they’re doing with their lives and she’s the only one who made it up as she went along.

and i say, gran, gran, really, NO. remember how i was going to be a veterinarian because i wrote that on a blue star in fifth grade? i didn’t know what i was doing. i just kept doing it.

i’m so relieved, she says, that you’re like me.

and i think, i am too, burvil. i am too.

***

***

***

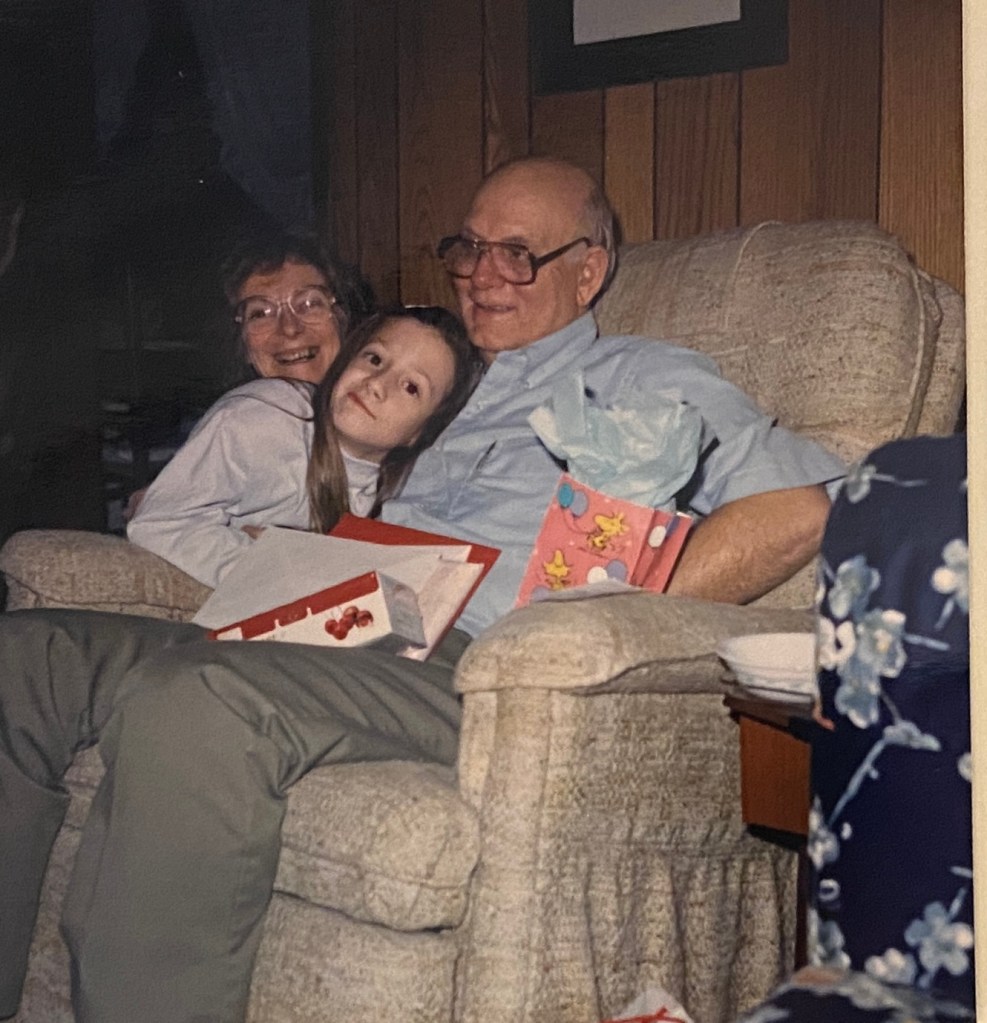

burvil slept until 11 on christmas morning.

because she’d been kept up by the sound of traffic the night before when she slept in the barracks with all us girls, she wound up spending christmas eve on the sofa in the living room and slept like the dead.

‘the kids can’t get to their stockings,’ giggled debo, ‘because their grandmother’s sleeping under the christmas tree!’

we all tried our darnedest and completely failed not to make a racket, eating breakfast at a whisper in the room next to where she slumbered. then the whole family, save gran, went back up to the barracks and sat and giggled and chatted and read for whole hours on end, waiting for her to wake up.

knowing that when she did, she’d likely kill us all for letting her sleep so long.

as it was, when she finally awoke, the refrain for the day was, ‘i’m mad at all of you!’ because we’d let her get the sleep she needed. because she suspected we’d had enormous fun without her. (it’s a family-wide phenomenon: this irrational fear that the time of everyone’s life will be had in one’s absence.)

during breakfast, as we sat speaking in hushed tones- shhhhhhhhing my father repeatedly because his level of general excitement is the antithesis of quiet- a horrible thought had occurred to me. what if burvil is dead? it was a horrible thought i’d felt absolutely dreadful having even had.

only later would it be discovered that we had each and every one of us been stricken by that thought and we had each and every one of us, independently, at various points throughout the morning, gone in to verify that burvil was truly sleeping. she was still breathing. she was, in fact, alive.

there’s a distancing at work here. in my grandparents’ evolution over the last years into joe and burvil. because they aren’t actually joe and burvil. they’re gran and pawpaw. they’ve always been gran and pawpaw. they will forever be gran and pawpaw.

but when i write about them, it’s somehow easier if they’re joe and burvil. if i treat them as adults. as people from whom i’m removed. people i’ve not seen in hospital gowns. people who are not so thin, so fragile that when i hug them, i can feel their bones.

gran and pawpaw are my grandparents. joe and burvil are LEGENDS.

***

***

***

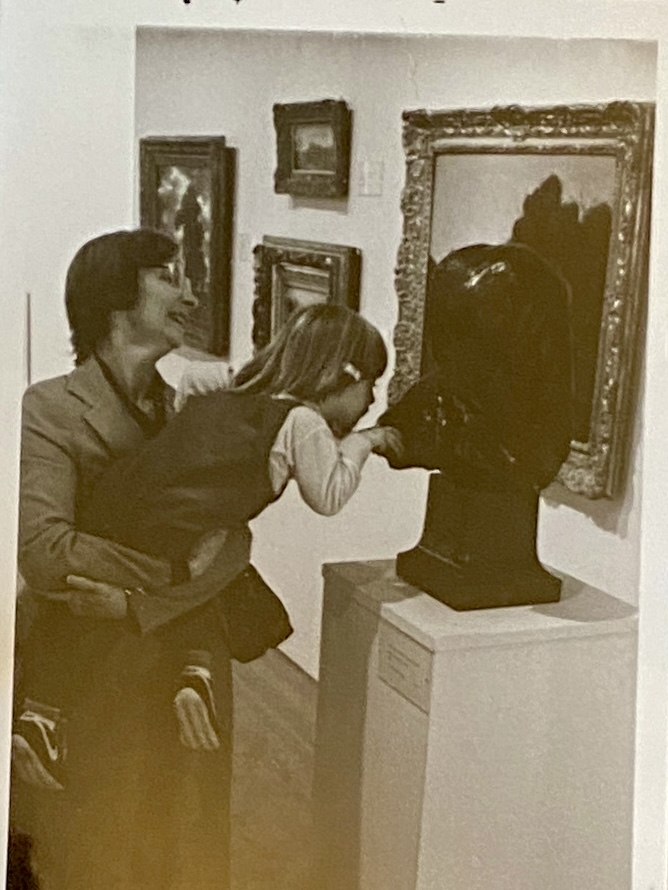

‘we were just talking about you,’ gran said. ‘there was a commercial for anne of green gables and i was telling your mother how much fun we had. you know, they’ll never really understand it. they’ll never really know. we had so much fun, you and i. how blessed we are to have ever had so much fun. years of fun.’

and suddenly, vividly, with a searing heat like a migraine in the heart, i’m reminded of all the nights i spent at her house, where she tucked me into bed and lay down next to me, book in her right hand, running circles along my back with her left until i, troubled sleeper even then, fell asleep.

***

***

***

***

***

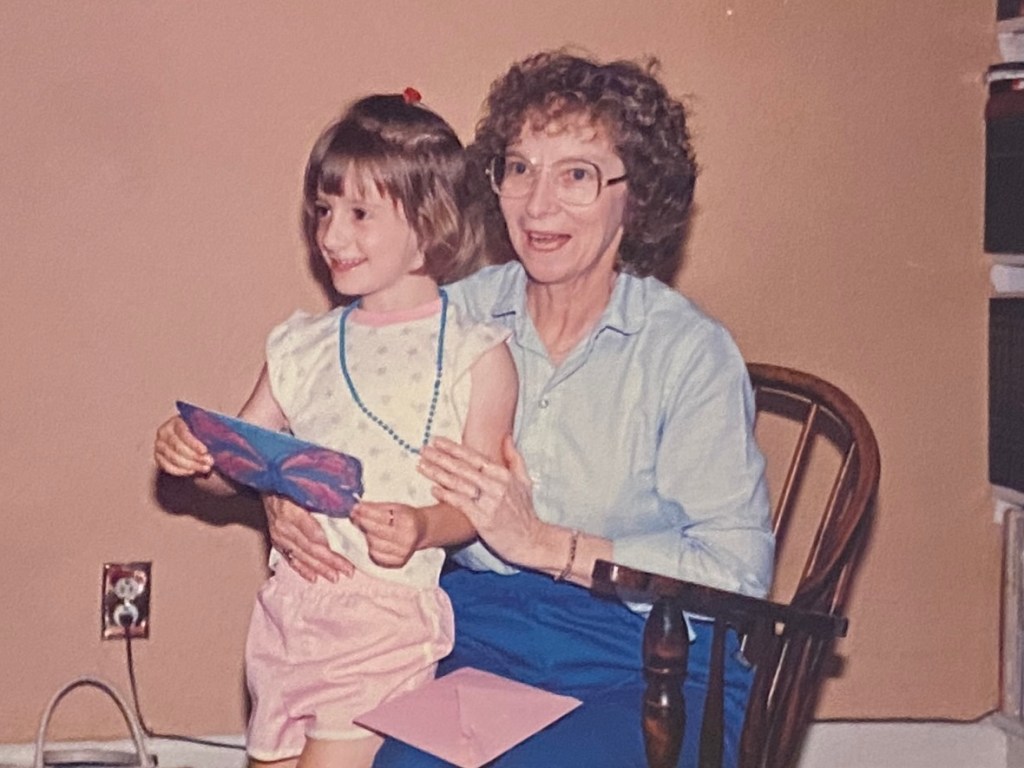

i spent a week with burvil down on the farm at christmas and, while it wasn’t exactly like old times- precisely because we are all older- it felt like a luxury. an extravagant one at that.

to be the beloved grandchild. to blow into town and have burvil call up all her octogenarian widow friends who no longer dare get behind the wheel and hear her boast to them that she has a driver who can take the whole lot of them up to walmart.

in 1986, in her ’86 buick with the cutting edge of technology power locks and power windows, burvil had rescued me from the hell on earth that was the harding academy summer camp. she lets me drive it now and flinches only ever so slightly when i, upon first getting in, confirm with her that i know the gas from the brake.

when leaving, i hugged her extra long, because in all the years that, in leaving her, i’ve not known if i’d see her again, this time felt somehow extra. the risk seems greater now. the impending loss edges closer.

***

***

***

in december of 2004, burvil fell and broke her hip. four days later, we spent a night together in the north mississippi medical center tupelo hospital during which both of us believed she was going to die.

this was my first brush with true disaster. having watched at least three documentaries on titanic, i felt fully prepared.

burvil fell on a tuesday. december 13th. she was standing on a stool pulling christmas decorations from a cabinet when she fell.

my grandfather wondered how long she lay there.

he and i sat at an empty orange table in the hospital cafeteria- the jello cup i bought with my own money stood abandoned between us- thinking of how this woman we’ve known for forever, this 75-year-old woman who had never before been broken, pulled herself across the unmopped kitchen floor and called him on the phone.

burvil fell on tuesday, december 13th. the day joe turned 74.

when we returned to her room, i encouraged everyone to leave. i swore i’d everything under control. when they departed, i stood at the door of room 204, waving, as though i had been accorded a tremendous honor i was grateful to be accepting on tv.

by the time they return in the morning, i will have worked everything out. the sanitized version of what happened that night. i will know how the story is to be told and that the punchline is: “burvil said ‘porno’!”

i will know there are things my parents must never know.

***

***

***

***

***

you just run up there and pull it out, she said. get it before they close the lid.

these were her instructions to her grandchildren for what to do about the gold filling on her upper right cuspid after she died.

they were to go up there together and get that thing out. for she, a child of the depression, didn’t want to be going into the ground with money in her mouth.

that tooth was gold. and girls, she said, you get it out.

***

***

debo texts:

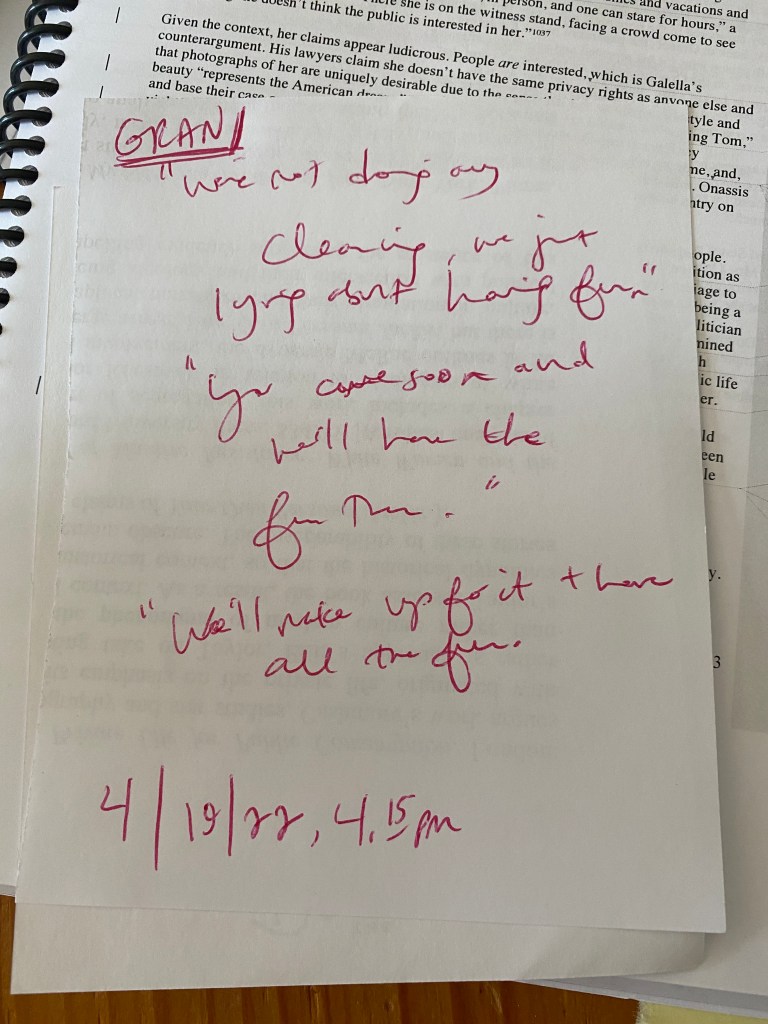

Gran was asking about you and where you are. She said she thought you had been here, but it’s good that she still knows you too ❤️❤️

and i have never been more certain that burvil is near death.

i call debo and she puts her on the phone. i write down what she says, because apparently my coping mechanism is to go into archivist mode. my coping mechanism is to write, to record, to bear witness, to shift the burden of what is happening immediately into my personal history and not the present.

(burvil did not die then. she lived on.)

***

***

***

***

***

i’ve so many sensory memories of my grandmother.

she’s not dead yet, as i write this. i’m not meaning to write like she is.

but she’s also not here with us in the way she once was.

i think she knew who i was when i last saw her. at the very least, she knew i mattered. it took a few minutes, but eventually she did smile.

when i would stay with her and joe in the house on inverness, she’d come lie in the bed next to me while i fell asleep. not touching. but in the bed on the other side. and the lamp on that side would be on and she’d lay there reading a book until i’d fall asleep.

and sometimes i’d close my eyes and jolt back awake, afraid she’d left me, and i’d turn to look, but the light was still on and she was still there next to me, reading.

i’ve had these nights where i have dreams and i wake up convinced she is gone.

and, still, she’s here.

and it feels like she is, in fact, going, albeit slowly. like she’s already half slipped away, as she used to do in the night, so i’d wake up in the sunshine and roll over expecting to find her, only to find that after however long, she’d left me to sleep.

***

***

***

burvil fell and broke her tailbone about a month ago. there’s a lady coming to stay with her during the day and help around the house. when i- burvil’s 33-year-old granddaughter- called yesterday, this lady answered. as she handed over the phone to burvil, who asked her who was calling, that lady told her, “it’s some little girl.”

it’s hard to call her gran because it’s hard not to say ‘gran and pawpaw.’ they were- after all- a pair.

i’m secretly relieved when she calls him joe. she has slipped only once when, exasperated by how many photographs she keeps finding- photographs tucked into every corner of the house, the attic, his workshop, the garage- she said ‘your pawpaw had more photographs than you could imagine.’ it was the exact same tone she used when she was short with him.

you can, apparently, still be short with someone, even when they are no longer there.

but it’s more than them being a pair. it’s actually very little to do with him, and mostly to do with her. her in that context- as gran. as my gran.

we’re talking once a week now at least and in these conversations we keep coming back to, she and i, the summer of 1986. when she quit her job at the law firm, bought a buick with power door locks (cutting edge then, now certified by the state of mississippi as an antique), and busted me free from the hell-hole that was harding summer camp.

i don’t remember complaining but, somehow, burvil knew. (burvil always knows.) she started picking me up early from camp. and every day, she came a little earlier until she suggested to debo that i should spend the summer with her.

and so we spent long days curled up on her couch under a blanket, giggling and watching judy garland and anne shirley over and over again.

entire years unfolded like this, as she would go on to pick me up every day after school, and i spent summers with her until we moved from memphis.

when i think of her as gran, in calling her that, i am that kid again, stuck between kindergarten and first grade, and she is a figure waiting beside a white buick, come to save me again.

she says, ‘we sure had fun. they’ll never know how much fun we had.’

and i tell her, ‘yes, we did. i think that’s when i fell in love with you.’

***

***

***

***

i dreamed there was a tornado at burvil and joe’s farm. upon entering the house after, i thought joe was dead, but knew he was just resting. he and burvil were old. suddenly they were gone and i was at the farm alone.

one of the themes of my dreams for quite some time has been finding unknown rooms in familiar spaces. it’s also been being brutalized in public while others watch and do nothing, but the rooms thing has been going on for longer, i think. i was in college, i think, when i dreamed of finding unknown rooms at graceland. i’ve been finding unknown rooms my whole life.

in this dream, with the tornado, burvil and joe were gone and both dead and, in this dream, i found two closets of joe’s that i’d not known existed. they had shag green carpet and a raised area, almost like a stage or like wings above a stage. the vibe was very much elvis presley’s jungle room.

and in these rooms were stuffed animals– real and imagined– from my life. all of them. saved and arranged with care on the upraised part of the closet.

what i felt in that moment in this odd dream was perfectly safe.

***

***

***

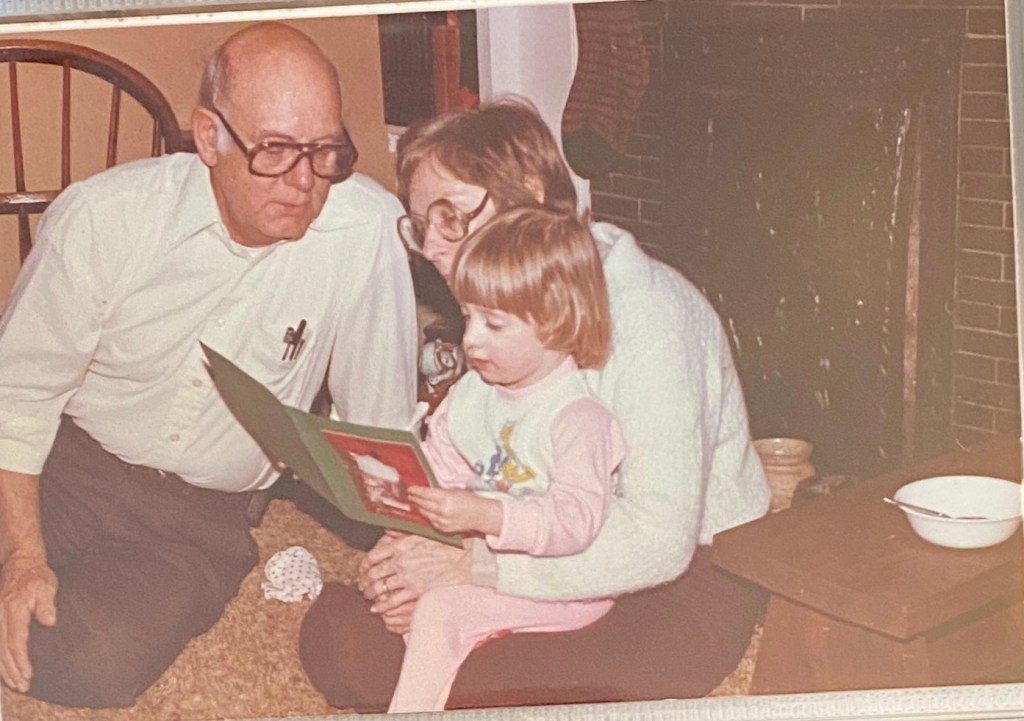

what i really remember is the weeks i’d spend at joe and burvil’s while we lived in atlanta. those three summers we were in atlanta, in particular, because the drama was so heightened by the fact that i was ten or eleven, that i’d gotten my period, that my parents were eight whole hours away, and that i was separated from my mother for THREE WHOLE WEEKS and we could only speak every other night because it was long-distance. the phone was rotary, fyi.

(please, let’s marvel that so many details of the above no longer exist.)

it’s amazing, just writing this, the nearness of feeling. as though there are these moments locked within us and if you’ll just take the time to put down a hundred words about them, every single sensation of some connected, deeply banal scene will come flooding back.

the nubbiness of a reclining chair. the cool of the air conditioning. the chill on bare legs. the hot air that rushed in when, after thirty minutes of yard work, burvil would open the back door and come back in the house, her skin radiating the heat, smelling of grass and sweat and ivory and white rain. and curled up in my coolness, every day i would say the same thing. gran, you smell like outside. and she would smile and put her warm hand on my cold one and, as she walked into the kitchen and my eyes returned to the TV, i would slip into my mouth another of the vanilla wafers from the cache secreted away in the pocket of my grandfather’s tattered reclining chair.

***

jean and lucy have brought uncle bill’s projector and two rolls of 8 mm home movies that are believed to have been taken during the childhood of my dead first cousin twice removed.

fyi- that is maybe one of the most southern sentences you’ll ever read.

joe is trying to work the projector. gary is helping by soliciting advice from online forums. they are both dreadful afraid of breaking the priceless family film.

it takes the first two hours of ABC’s airing of the ten commandments (including commercials) for them to get the projector working.

burvil makes popcorn.

debo dims the lights.

jean’s wedding is 27 seconds long. the halloween party of my dead first cousin twice removed, then seven, lasts a solid minute and a half.

after those 117 seconds, we five sit there in the dark, the whir of the projector the only noise until the slap of the film reel’s end.

and burvil says quietly, “the popcorn may not have been necessary.”

***

***

***

when burvil heard i was dying my hair red, she counseled that red hair was a good thing. because “people always remember redheads.” as she always is, burvil was right. they do.

***

***

***

***

***

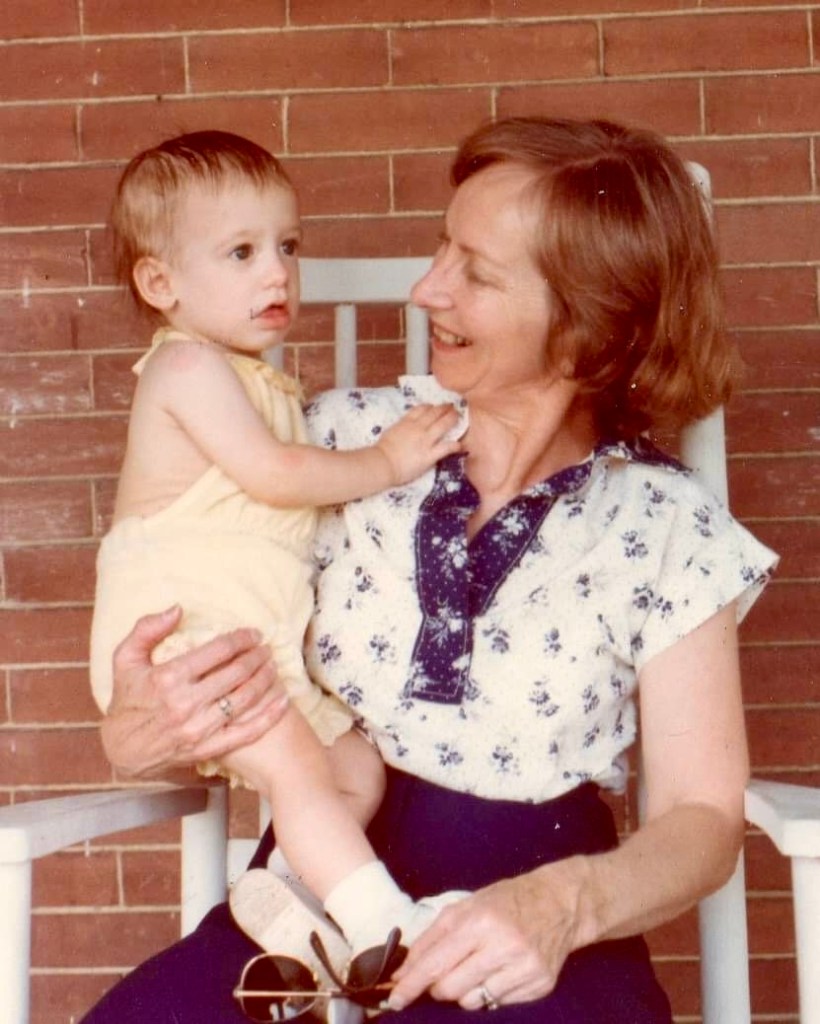

after we moved to atlanta and nashville, my parents would pack me off to my grandparents in memphis every summer. for either two sets of two weeks or one big, fat four week stretch.

this was a pattern that, in retrospect, was both a huge blessing and a horrible curse. it allowed me weeks at a time of unadulterated grandparental attention- attention that bolstered my belief in my own ability to do anything in ways i will probably never fully know. it also put me in memphis during the most intolerably hot time of year in an era when neither central air nor telephonic technology were all that they should have been.

because long-distance phone calls were still prohibitively expensive (to the extent that i remember begging my parents to let me call libby and nearly dying of elation when, once every six months, they relented), there was an undercurrent of sadness to these trips. i talked to my parents maybe once a week. i vividly remember one trip when i had a photograph of my mother (circa 1993, wearing a power suit and inexplicable dutch wooden shoes) that, in the privacy of my room, i would gaze upon whenever i was overcome with loss.

we did not yet have the context of being in mississippi for comparison, so in those days, being in memphis was like traveling to the ends of the earth. i read books about pioneers and commiserated. i too had ventured to an untamed land.

my grandfather was working then and, for some reason, my memories of these trips are spotty at best. all involve my grandmother and most are just little sensory snapshots of fleeting moments here and there.

the vivid sweetness of her spaghetti sauce, which ran so red with watered down canned tomato paste that it would stain my teeth, such an exciting phenomenon to my young self that i would tuck into bowl after bowl only to spend shameful amounts of time before the mirror staring at what my gran referred to as my “tomato smile.”

the sumptuous, cold thickness of the milk in her fridge. at the time i attributed this to my grandmother’s magical powers. only later would i learn it was the difference between skim and 2%.

the feel of my grandmother reading in bed beside me as she waited for me to fall asleep each night, one hand holding her book, the other running over and over and over through my hair, each caress stirring up the gentle scent of her white rain shampoo that i used every morning because, more than anything in the world, i wanted to be like her.

there has been no other time in my life quite like those summers. i like to think that had someone told me they were going to end, i would have savored them more. as it was, i took so terribly much for granted.

my grandmother is 81 now. we hug awkwardly, both of us too aware of our bodies. her bones poke through papery skin like a newborn kitten’s. she makes me feel too tall, too strong, too alive. i don’t thank her nearly enough.

i’ve never told her that because, during those summers, she watched soap operas while doing laundry, as an adult i cannot iron without humming the theme from as the world turns.

***

a few years ago- just before christmas, on my grandfather’s birthday- my grandmother fell and broke her hip and early on in the long year of the doctors putting her back together, she and i shared this nightmarish night alone together in a hospital in tupelo, mississippi. everyone else was exhausted and they all went home. so it was me and her alone at such a late hour our manners prevented us from summoning everyone back for help.

so we sat in her room just looking at each other, waiting.

it was the only time i’ve heard my grandmother say the word “porno.”

we were both of us convinced she was going to die.

she didn’t.

there are moments, random tiny fleeting glances during the hour or two we have together every three or four months now, when she catches my eye with a look that i can only feebly describe as quiet pride and unmitigated grit. i don’t know what it means. only that it has something to do with the night she didn’t die. something to do with me having been there.

she’s a tough one. friday night, my grandfather sat in bed- tears shining in his eyes, spilling down his cheeks, falling onto his bandaged hand that was holding mine- his voice cracking as he talked about how proud he was of her.

their victories are precious. coming off calcium shots. good blood pressure readings. no fluid in the lungs.

she’s a tough cookie, he said, but the women in my family aren’t always as tough as they look.

in the wee hours of friday morning, when he was hospitalized for the side-effects of a heart attack he didn’t know he had suffered three weeks before, my grandmother pulled herself up to her full 4 feet, 9 inches and pulled everything together. she grabbed his toothbrush, his wallet, the phone charger, the roller-board of medicines and the neatly typed list of all their names. she rode in the ambulance. she filled out all the forms. she made it look very easy.

only later did she admit she’d forgotten to put on any underwear.

***

***

The Memphis summer was so hot that the icing on my birthday cake melted on more than one occasion.

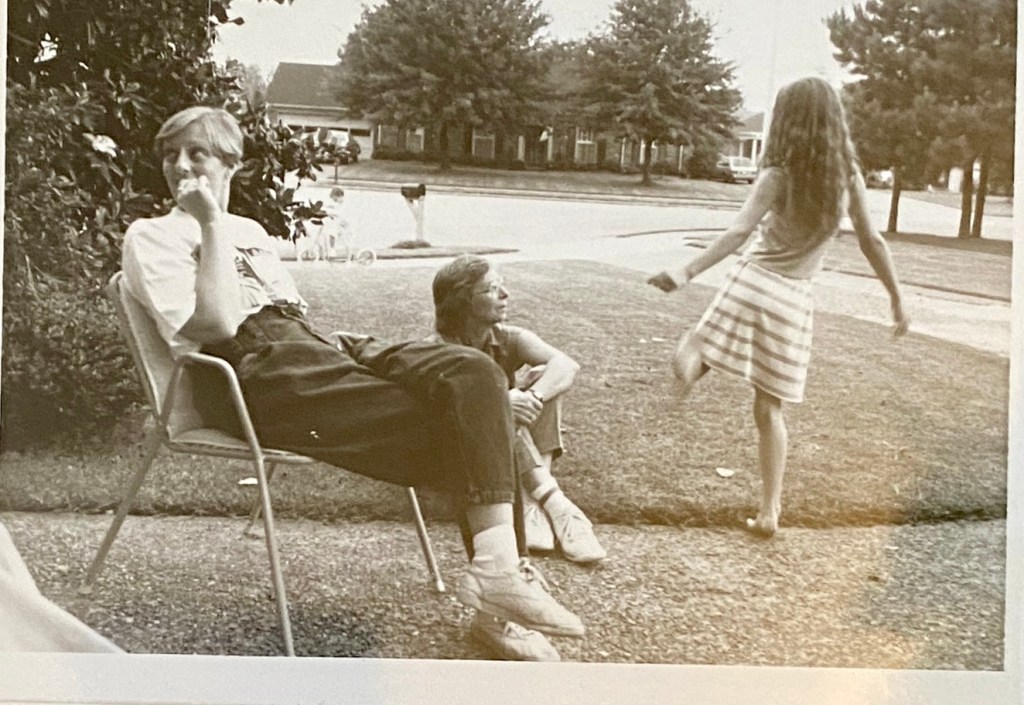

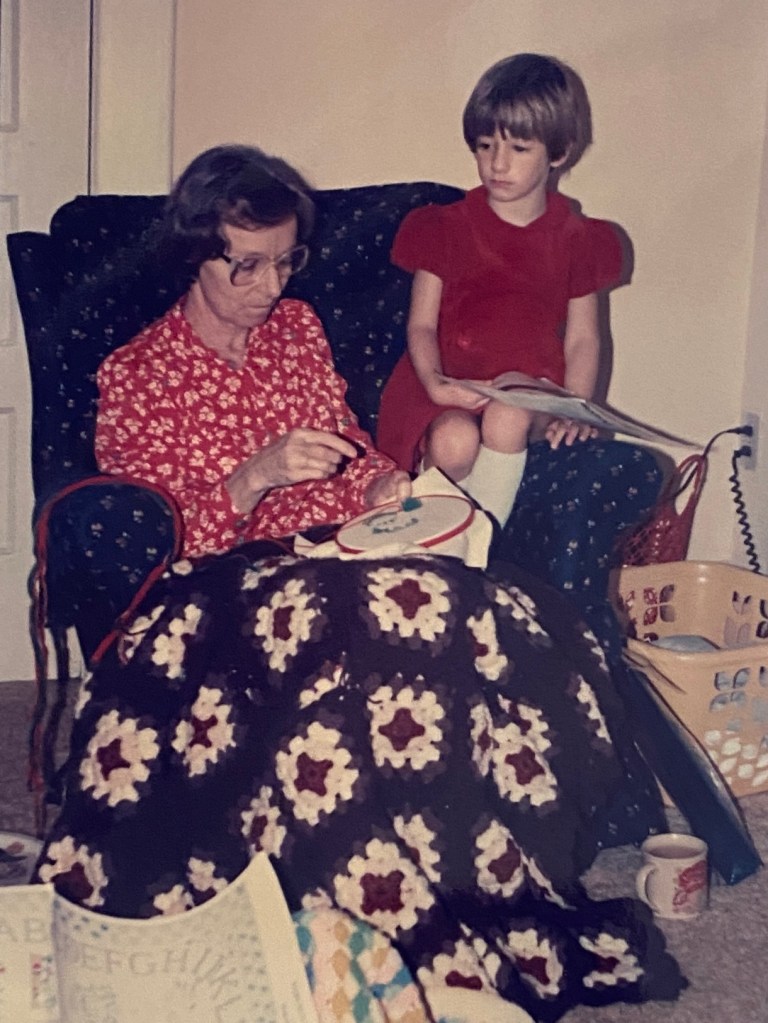

On summer evenings, my grandfather would buy a watermelon from the cart on Cleveland and we’d sit on the porch and devour it. Given strict instructions not to be “a priss,” I let the juice drip down my dress, the seeds stuck to my knees. My gran sat on the porch swing swatting mosquitoes and sewing.

She would rock back and forth, back and forth until dusk, when- because she was always furthest from the citronella candle, the scent of which made her eyes water- the fireflies would descend around her, their lights hitting the red in her hair and the red of the bricks in such a way that, for years after, I would take it for granted that she was a fairy and that those evenings were enchanted.

We all lived in Memphis then. We shared weeknights and Saturday afternoons and Sunday suppers. On vacations, we’d pile into my grandfather’s van. A van that, curiously, had no back seats so- in a move that was the single most hicktastic thing my family has ever done- we would pitch lawn chairs where the seats should’ve been.

My grandmother asks: Remember how we would put you up in the van on a pile of phone books and go on a great adventure?

And I have to say no because I do not remember the phone books. I only remember the adventure.

The pair of us sitting in the very back of the van, my white plastic lawn chair with the white and green woven plastic seat pushed as close to hers as it would go so I could lay my head in her lap while her pencil scratched against the page of the word search puzzles book that she rested on my back. I would lie there listening. To the scratch of her pencil and the sound of my grandfather, alone in the front seat, chewing peanuts and humming along to the big band music playing on NPR.

Words, music, magic. That is what I remember.

***

***

***

my grandmother got a blood clot in her eye when she was 36. it permanently damaged her vision, leaving her with a viewpoint that she likens to looking through an unsteadily held kaleidescope with a cracked lens.

i never knew this. that when she read all those biographies i lent her, the words were tap-dancing through a tie-dyed haze. i didn’t know until last christmas, when my grandfather was in the hospital and my grandmother nearly engaged the hematologist in fisticuffs because he didn’t concur with her views on plavix. suddenly all everyone talked about was the Great Blood Clot of ’65, and finally i understood why my grandmother owned a buick she didn’t drive.

my grandfather is in the hospital again.

my father called this morning and, in the frenzied timbre his voice takes on in times like this when he hasn’t slept or stopped thinking for 32 hours straight, he said it was scary. scarier than the last time.

which is scary because last time was the scariest thing any of us had ever seen.

he talked about pawpaw. about my mum. about the ICU visitors policy. he asked about me. and i asked about my grandmother.

my gran burvil. age 81. 4 feet 9 inches. 92 pounds.

this is the woman who rescued me from swimming lessons and the harding academy summer camp.

she loves birds and the color blue.

she makes the best spaghetti in the south.

she wheels my grandfather’s medicines around in a rollarboard.

afraid of the computer, she typed out two copies of his complete medical history on her IBM selectric- one went in her wallet, one in her bible.

she once threatened to ditch the ridgeway baptist church golden agers group on the side of highway 78 because they were talking shit about mississippi.

this is my grandmother.

the irish farmer’s eldest daughter.

we are a lot alike.

we had a fight this past christmas. our first in years. because she was sad and i was sad and, after enduring a tutorial on how to properly cut bananas, i had the audacity to pour the pudding into the trifle wrong, making everything go kaboom.

(in true eaton family fashion, there are pictures and they are lovely.)

we apologized the next day, both of us blubbering as we stood together in the dark of her sewing room, surrounded by scraps of the fabrics from the dresses of my childhood, a tiny streak of early morning sunlight streaming in through the window, highlighting the hint of red that still dapples her hair.

when i hug her now, she’s skin and bones. fragile like a kitten. yet still, somehow, tough as nails.

***

i’ve been running wild for the last nine days full of too many things.

all of which to say, my flat is WRECKED.

my father noted this when we skyped the other evening. he said, whoa. dartar, you’re looking a little squalid. eatonspeak for: CLEAN YOUR ROOM. which is what today’s for.

which is fortunate as last night i had a panic dream that i’d arranged to have two people from airbnb stay in my flat whilst steven was also visiting, one of whom was catsitting for a friend. fortunately, in the panic, i discovered a portal to a room from burvil’s 1980s house which had been secretly grafted onto my flat here in england, so ultimately all was well.

***

burvil’s best soundbites from thanksgiving, 2012:

(1) “i’d rather be whipped than eat an oreo.”

(2) “i’d rather just not eat than sit at a crowded table.”

***

***

burvil has died. and i’m in the shower, a month later, sobbing. not because i am sad but because i am so terribly grateful. to have been loved like that. to have loved like that. and because i know i will never be loved like that nor love like that again.

***

***

***

i’m watching my mother watch her mother.

we’re in a doctor’s office and there’s some show on with a panel of women, one of whom i’m pretty sure once dated rob kardashian, and i am simultaneously proud of myself for knowing this and wishing it were possible to turn the volume down.

we are terrified of catching the flu. (i am also strangely fearful of being shot but that’s a different story.) there is a kid in the room with a cough that sounds tubercular and a surgical mask he does not want to wear.

he goes to the bathroom right before burvil and, when she returns, i hose her down with hand sanitizer. we have sanitized to such an extent that i assume layers of skin have sloughed off before recognizing a clump of sanitizer remains unblended.

there is a very real sense that death is near- if not from gun shot or flu then surely from e coli.

the pipes have burst. we are bringing water in from buckets placed in the lawn in order to flush the toilets.

we are tensed, we are poised, we are waiting for something that has yet to come but we know it ain’t good.

i get up every morning and write. like nothing has happened, nothing is happening, nothing nothing except the world in my head.

i marvel at how elastic i am. at how elegantly i sustained the blow of my life’s uprooting, of my expulsion. i marvel at how little i feel the hurt.

inevitably there is leakage. nosebleeds intrude.

it feels like a hurricane has come through. just after a train wreck.

flooding on whiplash.

my shoulders feel like i imagine they would if i ever went for a vigorous swim.

i am pregnant with metaphors!

hemmed in by writing deadlines. stuck in ways i do not understand, which do not always hurt but are not entirely pleasant.

we are all of us stuck in ways we do not understand.

there comes a point in time and age where your bones cannot support you and they break of their own volition.

***

***

***

last night, joe and burvil and i attempted to skype. the results were… mixed. on the one hand, they could never hear me and i could only ever see the tops of their heads. on the other hand, i could hear them perfectly and they could see me. thus, burvil could see when i started giggling and i could hear her peals of laughter. so win/win, really. except for the whole having a conversation part.

***

***

***

***

***

the thing about the banana trees in america is that they cannot handle the winter. they have to be unplanted and packed away for the cold months. burvil used to put hers in the attic.

in order to live, they must be uprooted and packed away. but then the spring comes again and then the summer, and they stretch themselves, grandly lifting their green selves up towards the sun.

that’s it. that’s the ending. the banana trees will be back. let me just put my little faith in that.